Case discussion

In the online country guide of Do we have a deal? I discuss a case study: Willems doesn’t get his way. The reader of the book recognizes the cultural differences and the dimensions that explain the differences, allowing the reader to be better prepared and act more effectively in similar circumstances.

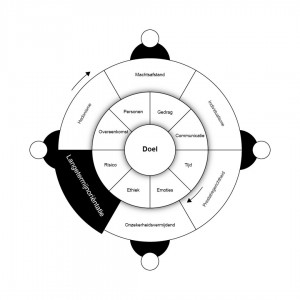

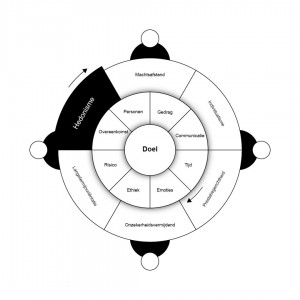

The following are some handouts:

Case discussion

The negotiations Willems faced were complex. The context was multicultural and there were many interests. Despite the fact that seemingly only one should matter: protecting the vulnerable population. But it was not that simple, and Willems drew the short straw.

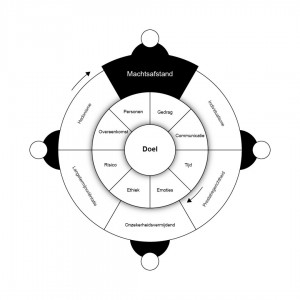

What was Willems all about?

Which individuals participated in the negotiations and what was their role in it? Who was at the table and who was not? We saw the relationship between Willems and the minister. The secretary general played a role, as did the leaders of the British, French and German aid organizations. Willems pulled the cart, but needed these others to achieve his goal. Willems also had to deal with decision-makers in the partner countries that were invisible to him. There were also the Chinese and the American supplier in the background. And the president, of course.

With what purpose did they enter the negotiations? All parties wanted the population to be able to be warned in time in case of another tsunami. But could ethnic tensions, cost-benefit analysis and insecurity change those goals? And did the Englishman represent the supplier’s interest?

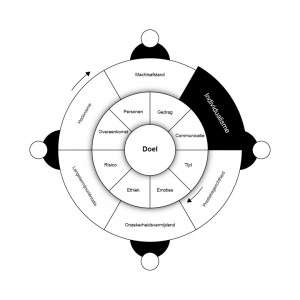

What were their behavioral dispositions? What was their basic attitude and personal style in the negotiations? Willems was open and very results-oriented, while Ratnayeke never allowed himself to be caught off guard and even scolded Willems at times. At least that’s how Willems might take it. Except for the Frenchman, the other Europeans seemed to keep a low profile.

How did the negotiators communicate and what did words, gestures and other forms of expression mean? There were hardly any discussions at a round table where everyone could pitch their ideas. Willems dealt with many casual conversations and encounters that were filled with allusions.

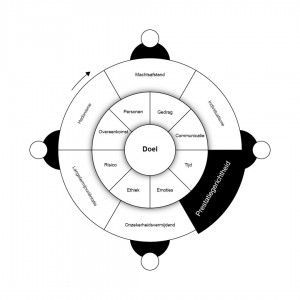

What does time mean and how sensitive were the negotiators to time factors? Willems and the English wanted to move forward. The Frenchman trotted and Ratnayeke and his entourage seemed to have all the time in the world. There could be another tsunami tomorrow!

How did people deal with emotions and what did they mean. Willems struggled to hide his annoyance and shot on the defensive in frustration. Ratnayeke showed little emotion, although his kindness to Willems initially seemed genuine. If Ratnayeke would have had any emotions at all, Willems did not get to see them. The minister, his friend became unreachable.

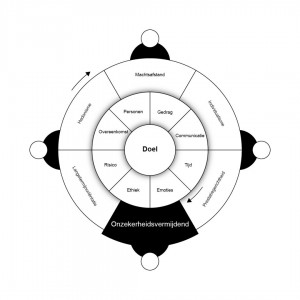

What was good and what was evil. Willems could not imagine that people would be without a warning system for so long, and what agenda did the British and Chinese have. This project was his, wasn’t it?

Did Willems take too much risk with his claims about the East? And couldn’t the Germans have waited with their endless calculations until the project was confirmed?

It never came to an agreement, but the letter of intent he had drafted left little to be guessed at. He even had the Germans’ detailed specifications attached. Actually, it was also more than a statement of intent. It was, in fact, a draft agreement.

Willems had a lot to think about. Understanding cultural differences can explain much, and the cultural dimensions we discuss in this book might not have given him a guarantee of success, but at least a better basis for getting down to business.

Willems’ French colleague from our example could not make decisions. His superiors in France had not given him a mandate. Willems, on the other hand, acted under the adage “no news, is good news. He could judge for himself when higher hands needed to be called in. The secretary general sat with pen and paper ready when the minister was present, but made Willems wait when he visited him.

Minister Ratnayeke never said what was on his mind. And then that secretary general who sat in such a high position despite the incompetence that Willems attributed to him. Just because he would be the nephew of a former president?

Willems had to experience how the English eventually trounced him. They had previously complained about slow decision-making and had gradually chosen eggshells for their money. It was not clear to Willems whether his English colleague had helped the English company get the Chinese contract, but the company had clearly chosen to profit. With or without the Europeans.

Willems marveled at the lack of incisiveness of his French colleague, as well as the drivel about details of the eternally “sietzende” German colleague. Fortunately, he had not included the Spanish in the collaboration. Those just push everything to “mañana. The Brit in the alliance was a lot more decisive, but also kind of short-tempered. Occasionally.

Willems was trounced by the Chinese, while the British got away with the material spoils. Not with the moral spoils, Willems and his colleagues felt, which had been lost.

Willems was outraged at the British for making the deal with the Chinese behind his back. Those Brits must be having a lavish party with the Chinese now, he thought. But he didn’t have to be so afraid of that. The British do like a “pint in the pub,” but the Chinese don’t get you on the table so easily.